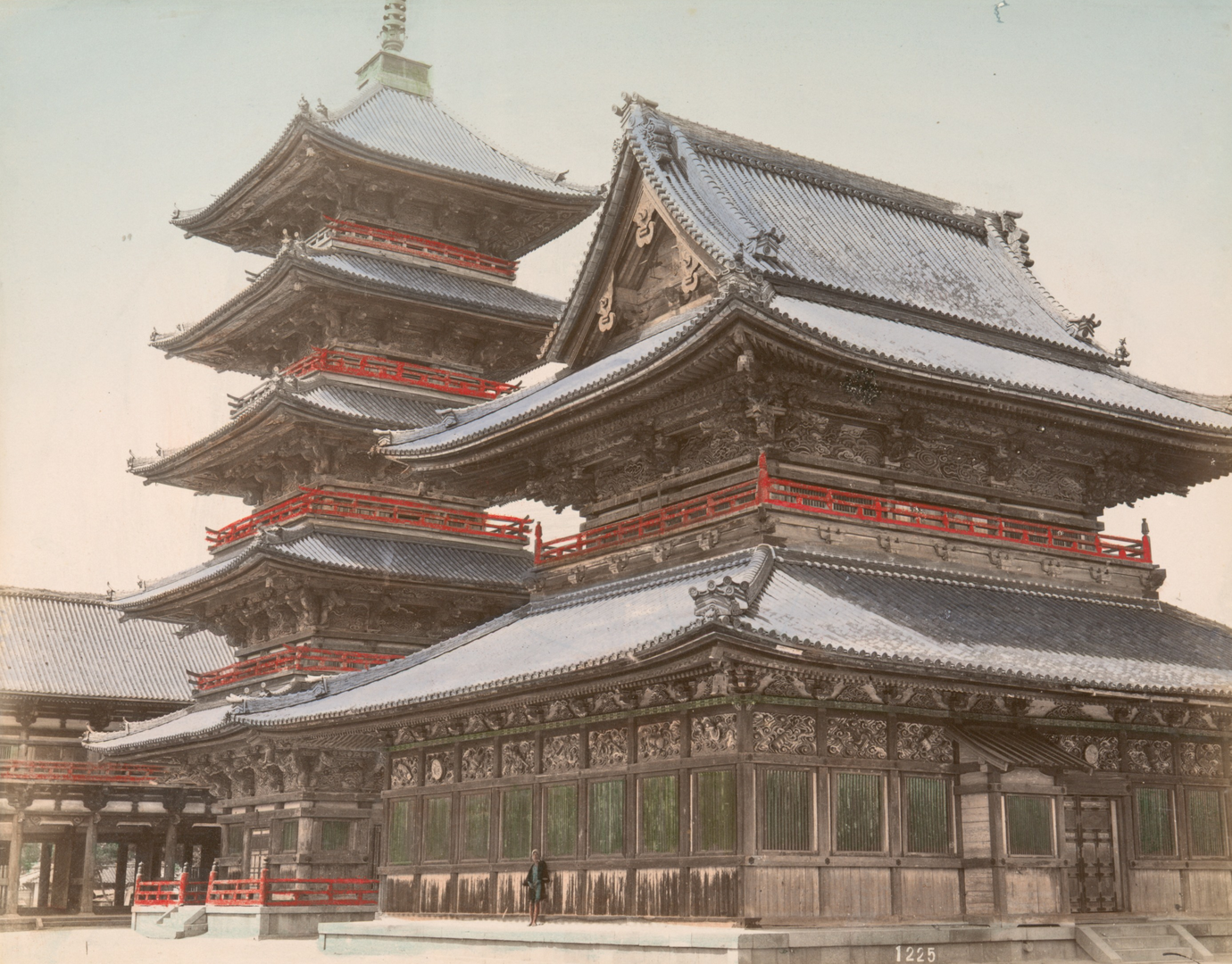

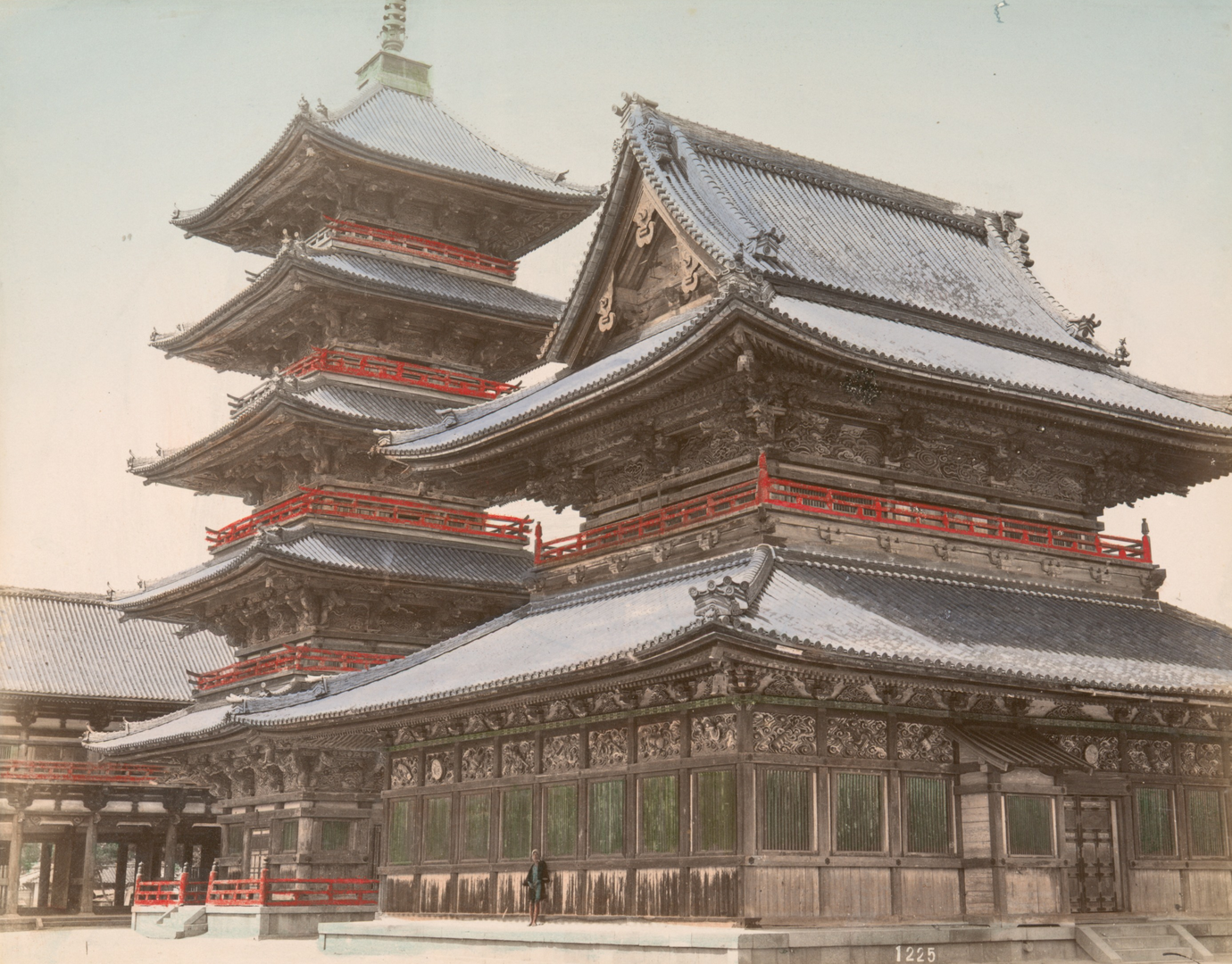

Image from New York Public Library, via Wikimedia Commons

If you visit Osaka, you’ll be urged to see two old buildings in particular: Osaka Castle and Shitennō-ji (above), Japan’s first Buddhist temple. In beholding both, you’ll behold the work of construction firm Kongō Gumi (金剛組), the oldest continuously run company in the world. It was with the building of Shitennō-ji, commissioned by Prince Shōtoku Taishi in the year 578, that brought it into existence in the first place. Back then, “Japan was predominantly Shinto and had no miyadaiku (carpenters trained in the art of building Buddhist temples),” writes Irene Herrera at Works that Work, “so the prince hired three skilled men from Baekje, a Buddhist state in what is now Korea,” among them a certain Kongō Shigetsu.

Thereafter, Kongō Gumi continued to operate independently for more than 1,400 years, run by 40 generations of Kongō Shigetsu’s descendants. By the time Toyotomi Hideyoshi had the company build Osaka Castle in 1583, it had been established for nearly a millennium. In the centuries since, “the castle has been destroyed repeatedly by fire and lightning,” Herrera writes. “Kongō Gumi prospered because of these major reconstructions, which provided them with plenty of work.” Throughout most of its long history, an even steadier business came from their specialty of building Buddhist temples, at least until serious challenges to that business model arose in the twentieth century.

“World War II brought significant changes to Japan, and the demand for temple construction waned,” says the tourism company Toki. “Sensing the shifting tides of the time, the company made a strategic decision to pivot its expertise towards a new endeavor: the crafting of coffins.” Governmental permission was arranged by the widow of Kongō Haruichi, Kongō Gumi’s 37th leader, who’d taken his own life out of financial despair inflicted by the Shōwa Depression of the nineteen-twenties. Here time at the head of the company illustrates its long-held willingness to grant leadership duties not just to first sons, but to family members best suited to do the job; for that reason, the history of the Kongō clan involves many sons-in-law deliberately sought out for that purpose.

The combined forces of the decline of Buddhism and the popping of Japan’s real-estate bubble in the nineties eventually forced Kongō Gumi to become a subsidiary of Takamatsu Construction Group in January 2006. “The current Kongō Gumi workforce has only one member of the Kongō family,” the Nikkei Asia reported in 2020, “a daughter of the 40th head of the family” who “now serves as the 41st head.” But its miyadaiku — distinctively organized into eight independent kumi, or groups — continue to do the work they always have, with ever-more-refined versions of the traditional tools and techniques they’ve been using for nearly a millennium and a half. Kongō Gumi continues to receive international attention for maintaining its high level of craftsmanship, but viewers of American TV drama in recent years will also appreciate that its having solved the problem of succession.

Related Content:

Why Japan Has the Oldest Businesses in the World?: Hōshi, a 1300-Year-Old Hotel, Offers Clues

Building Without Nails: The Genius of Japanese Carpentry

A Visit to the World’s Oldest Hotel, Japan’s Nisiyama Onsen Keiunkan, Established in 705 AD

See How Traditional Japanese Carpenters Can Build a Whole Building Using No Nails or Screws

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.