Missing from the ongoing discussions regarding President Jimmy Carter’s legacy following his Dec. 29 passing are the former Democratic president’s crucial efforts to save and modernize historically Black colleges and universities. The survival and subsequent expansion of HBCUs represents a meaningful achievement within Carter’s complex presidential record, which is forever marred by his resounding defeat after one term by his Republican successor, Ronald Reagan. Ironically, Reagan ran a vigorous campaign against another landmark aspect of Carter’s educational legacy—the establishment of the Department of Education in 1979, which played a crucial role in Carter’s efforts to support HBCUs.

Conventional wisdom might suggest that Carter—who garnered overwhelming support from African Americans and who, for many, was a champion of civility, education and human rights—would have unconditionally supported Black colleges. Instead, the presidential son of the South, largely raised by one of his father’s Black sharecroppers, faced an uncertain path to securing HBCUs’ futures. The institutions themselves grappled with questions of survival; desegregation politics were at play. During Carter’s presidency from 1977 to 1981, the aftermath of civil rights advancements was reshaping the American political landscape, and HBCUs confronted genuine threats of closure.

The Downturn of HBCUs Within a Racially Integrating America

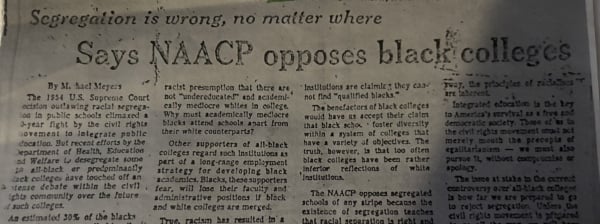

“Segregation is wrong, no matter where,” declared a Jan. 6, 1979, editorial in The [Cleveland] Plain Dealer by Michael Meyers, a director of research and policy for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. The subhead announced the NAACP’s opposition to Black colleges.

The renowned African American civil rights organization’s Legal Defense Fund, led by white attorney Jack Greenberg, promoted this view as part of its most radical and controversial efforts to eliminate all forms of racial grouping in the nation. Not all members of the NAACP-LDF classified HBCUs as segregated institutions, though federal lawsuits filed by the organization implicated Black colleges on those grounds. The legal question regarding issues of racial diversity at historically Black versus predominantly white colleges initially remained unresolved in the litigation known as the Adams cases.

To be clear, the NAACP-LDF opined that they did not intentionally push for the “desegregation” of HBCUs, yet members of the Black college community accused them of such. On April 1, 1977, federal judge John H. Pratt issued an order that sought to clarify the issue. Pratt ruled that “the process of desegregation must not place a greater burden on Black institutions,” including HBCUs, and instructed Carter’s Department of Health, Education and Welfare to “devise criteria for higher education desegregation plans which will take into account the unique importance of Black colleges and simultaneously comply with the congressional mandate” to racially desegregate American colleges. Suffice to say, HBCU leaders were nervous about how Carter’s HEW would interpret and apply the legal order to their institutions.

“Integration must never mean the liquidation of Black colleges. If America allows Black colleges to die, it will be the worst kind of discrimination and denigration in history,” cried Benjamin Mays, president of Morehouse College and renowned civil rights activist, encapsulating the HBCU stance on the issue. The Carter administration became the primary target of an enraged collective of educated African Americans who were resolved to leverage their degrees, institutions, jobs, resources, activism, media and influence to not only preserve HBCUs but also maintain their predominantly Black identity within a racially desegregated America.

HBCUs in Crisis

The HBCU integration saga was just one of several crises faced by Black colleges during Carter’s single term as president. The precariousness of Black colleges became evident a little more than a year after Carter assumed office when, on May 22, 1978, Anita Allen, the HEW education financial manager, circulated an urgent memo titled “Black Colleges in Distress.” While Allen acknowledged the long-standing economic assault on HBCUs by describing them as “financially starved,” she warned that “the Administration is currently in a position to close down most of the historically Black private institutions, which receive over 90 percent of their funding from the Federal Government, primarily through student financial aid grants.” Allen provided extensive details about how HBCUs failed to meet federal regulations; nonetheless, she insisted, “It is my position that the Black community does not support or condone the elimination of [HBCUs] … in the name of desegregation … [or] in the name of efficiency in the collection of loans.”

While Allen encouraged Carter to err on the side of caution and leniency concerning HBCUs, Joseph Califano, Carter’s HEW secretary, was not fully viewed as a pro-HBCU official. In fact, he publicly questioned the stability and worthiness of Black colleges, asking, on June 23, 1978, “Even with the money we give some of these schools, as they now operated, are they viable institutions?”

His sentiments angered HBCU advocacy leaders, who feared an anti-HBCU secretary of education who could undercut the institutions’ political interests. They responded strongly on behalf of their institutions. On July 6, 1978, the Carter administration received a coordinated and impassioned wave of correspondence requesting a meeting. After extensive internal discussion, the request was granted.

A Transformative Meeting

“We fear a tragic and unnecessary rupture between our colleges and your administration,” the HBCU leaders warned during the resulting meeting with Carter and Vice President Walter Mondale. More than 60 prominent HBCU representatives joined the Aug. 18, 1978, meeting held in the White House Cabinet Room. Although the tone was cordial, the discussion was far from uncritical of the Carter administration’s insensitive (albeit unintentionally so) handling of Black college affairs up to that point. Recounting a history of federal and White House hostility toward HBCUs, the Black college representatives conveyed to the president that they were now “fearful” that those who sought to use federal policy to close their colleges were “gaining the upper hand” in the Carter administration. Ultimately, the Black college advocates sought increased federal investment in HBCUs through strong, long-term federal policies that addressed the ways chronic discrimination and underfunding had harmed the institutions since their inception, in 1837.

“Heads of Black Colleges Seek More U.S. Support,” read a headline in The Washington Post a day after the meeting. It was one of many such media stories relating accusations that Carter, a friend of the African American electorate, was undermining HBCUs. Something needed to be done to counter the negative narrative.

It was coincidental that the long-standing challenges faced by HBCUs peaked as Carter assumed the presidency. As former governor of Georgia—a state with a rich culture of HBCUs, particularly in Atlanta, home to Morehouse and Spelman Colleges—Carter had built ties with the Black college community there. He counted Martin Luther King Sr., Benjamin Mays, Andrew Young and many other notable HBCU graduates or advocates as personal friends. Carter understood firsthand how HBCUs empowered the nation by uplifting Black people. At that time, he held the record for hiring the most African Americans in any presidential administration and for appointing the most African American federal judges—many of whom were HBCU graduates.

HBCUs as a Presidential Priority

So when the proposal to make HBCUs the first American educational institutions to have their own White House office reached Carter’s desk, he enthusiastically agreed. On Aug. 8, 1980, on the White House lawn, Carter signed Executive Order 12232 establishing the White House Initiative on Historically Black Colleges. HBCU advocates within and outside the Carter administration achieved their goal of placing their colleges under the remit of the White House, giving them direct access to the American president.

There was just one problem: Three months later, Carter lost the presidency to Reagan, who had campaigned against increasing federal funding for education. But in a remarkable turn of events, Reagan, who supported neither affirmative action nor civil rights legislation, kept Carter’s Black college proposals alive and even expanded the White House Initiative on HBCUs.

Ultimately, it was Carter’s commitment to promoting the continuation of HBCUs within an integrated society and injecting significant federal resources into these institutions that saved and modernized Black colleges. New degree programs, better-trained faculty, improved facilities, more access to grants, increased corporate investment, more scholarships, stronger congressional support and heightened popular culture acclaim are all tangible outcomes from Carter’s revitalization of Black colleges.

Each successive American president has pursued Carter’s vision by supporting the White House Initiative on HBCUs and Black colleges over all. Without the bipartisan federal support that began with Carter’s presidency during a challenging time for HBCUs, these institutions might not exist today, at least not in their current, predominantly Black forms.