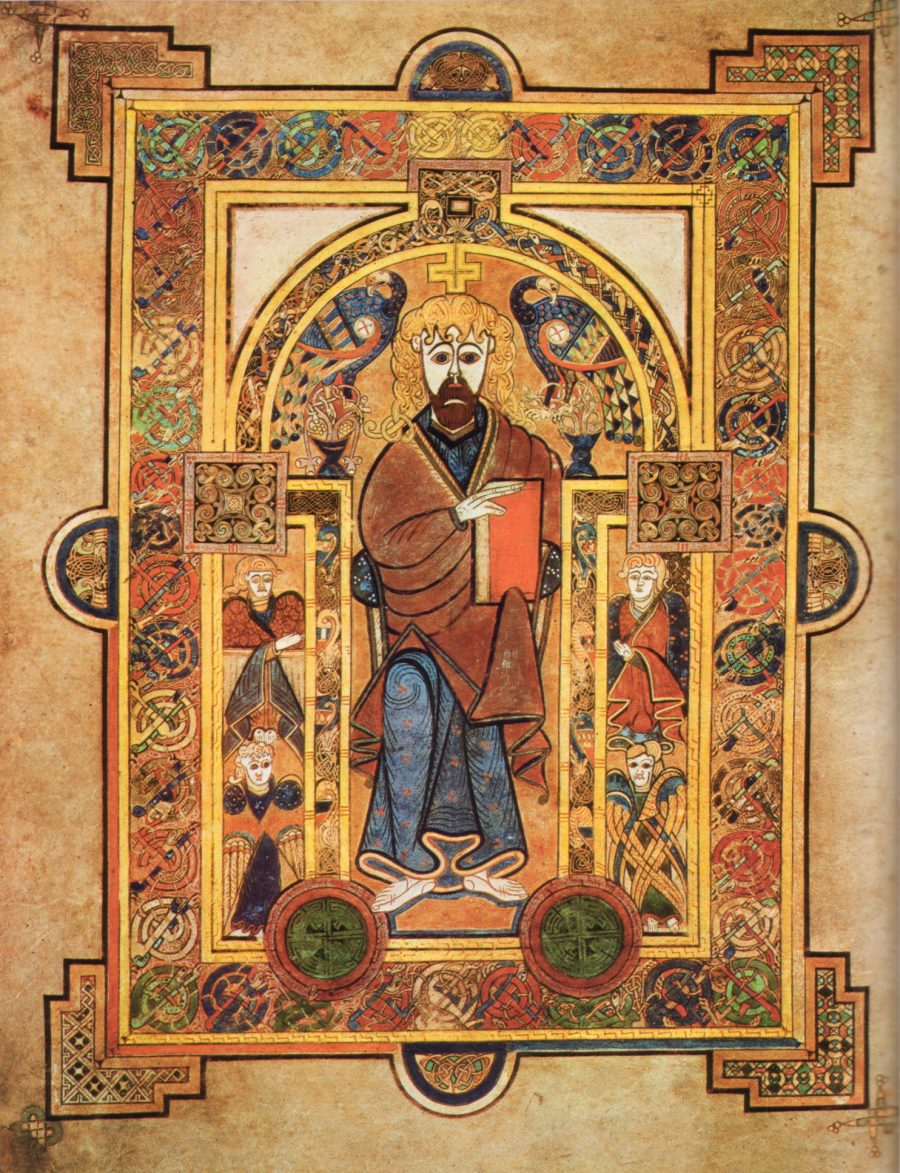

If you know nothing else about medieval European illuminated manuscripts, you surely know the Book of Kells. “One of Ireland’s greatest cultural treasures” comments Medievalists.net, “it is set apart from other manuscripts of the same period by the quality of its artwork and the sheer number of illustrations that run throughout the 680 pages of the book.” The work not only attracts scholars, but almost a million visitors to Dublin every year. “You simply can’t travel to the capital of Ireland,” writes Book Riot’s Erika Harlitz-Kern, “without the Book of Kells being mentioned. And rightfully so.”

The ancient masterpiece is a stunning example of Hiberno-Saxon style, thought to have been composed on the Scottish island of Iona in 806, then transferred to the monastery of Kells in County Meath after a Viking raid (a story told in the marvelous animated film The Secret of Kells). Consisting mainly of copies of the four gospels, as well as indexes called “canon tables,” the manuscript is believed to have been made primarily for display, not reading aloud, which is why “the images are elaborate and detailed while the text is carelessly copied with entire words missing or long passages being repeated.”

Its exquisite illuminations mark it as a ceremonial object, and its “intricacies,” argue Trinity College Dublin professors Rachel Moss and Fáinche Ryan, “lead the mind along pathways of the imagination…. You haven’t been to Ireland unless you’ve seen the Book of Kells.” This may be so, but thankfully, in our digital age, you need not go to Dublin to see this fabulous historical artifact, or a digitization of it at least, entirely viewable at the online collections of the Trinity College Library. (When you click on the previous link, make sure you scroll down the page.) The pages, originally captured in 1990, “have recently been rescanned,” Trinity College Library writes, using state-of-the-art imaging technology. These new digital images offer the most accurate high-resolution images to date, providing an experience second only to viewing the book in person.”

What makes the Book of Kells so special, reproduced “in such varied places as Irish national coinage and tattoos?” asks Professors Moss and Ryan. “There is no one answer to these questions.” In their free online course on the manuscript, these two scholars of art history and theology, respectively, do not attempt to “provide definitive answers to the many questions that surround it.” Instead, they illuminate its history and many meanings to different communities of people, including, of course, the people of Ireland. “For Irish people,” they explain in the course trailer above, “it represents a sense of pride, a tangible link to a positive time in Ireland’s past, reflected through its unique art.”

But while the Book of Kells is still a modern “symbol of Irishness,” it was made with materials and techniques that fell out of use several hundred years ago, and that were once spread far and wide across Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa. In the video above, Trinity College Library conservator John Gillis shows us how the manuscript was made using methods that date back to the “development of the codex, or the book form.” This includes the use of parchment, in this case calf skin, a material that remembers the anatomical features of the animals from which it came, with markings where tails, spines, and legs used to be.

The Book of Kells has weathered the centuries fairly well, thanks to careful preservation, but it’s also had perhaps five rebindings in its lifetime. “In its original form,” notes Harlitz-Kern, the manuscript “was both thicker and larger. Thirty folios of the original manuscript have been lost through the centuries and the edges of the existing manuscript were severely trimmed during a rebinding in the nineteenth century.” It remains, nonetheless, one of the most impressive artifacts to come from the age of the illuminated manuscript, “described by some,” says Moss and Ryan, “as the most famous manuscript in the world.” Find out why by seeing it (virtually) for yourself and learning about it from the experts above.

For anyone interested in getting a copy of The Book of Kells in a nice print format, see The Book of Kells: Reproductions from the manuscript in Trinity College, Dublin.

Related Content:

Take a Free Online Course on the Great Medieval Manuscript, the Book of Kells

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness