The three princes of Sarandib—an ancient Persian name for Sri Lanka—get exiled by their father the king. They are good boys, but he wants them to experience the wider world and its peoples and be tested by them before they take over the kingdom. They meet a cameleer who has lost his camel and tell him they’ve seen it—though they have not—and prove it by describing three noteworthy characteristics of the animal: it is blind in one eye, it has a tooth missing, and it has a lame leg.

After some hijinks the camel is found, and the princes are correct. How could they have known? They used their keen observational skills to notice unusual things, and their wit to interpret those observations to reveal a truth that was not immediately apparent.

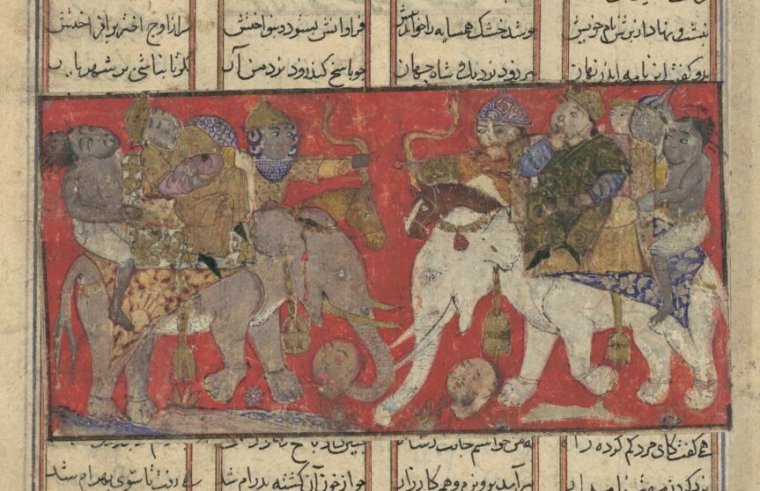

It is a very old tale, sometimes involving an elephant or a horse instead of a camel. But this is the version written by Amir Khusrau in Delhi in 1301 in his poem The Eight Tales of Paradise, and this is the version that one Christopher the Armenian clumsily translated into the Venetian novel The Three Princes of Serendip, published in 1557; a publication that, in a roundabout way, brought the word “serendipity” into the English language.

In no version of the story do the princes accidentally stumble across something important they were not looking for, or find something they were looking for but in a roundabout, unanticipated manner, or make a valuable discovery based on a false belief or misapprehension. Chance, luck, and accidents, happy or otherwise, play no role in their tale. Rather, the trio use their astute observations as fodder for their abductive reasoning. Their main talent is their ability to spot surprising, unexpected things and use their observations to formulate hypotheses and conjectures that then allow them to deduce the existence of something they’ve never before seen.

Defining serendipity

This is how Telmo Pievani, the first Italian chair of Philosophy of Biological Sciences at the University of Padua, eventually comes to define serendipity in his new book, Serendipity: the Unexpected in Science. It’s hardly a mind-bending or world-altering read, but it is a cute and engaging one, especially when his many stories of discovery veer into ruminations on the nature of inquiry and of science itself.

He starts with the above-mentioned romp through global literature, culminating in the joint coining and misunderstanding of the term as we know it today: in 1754, after reading the popular English translation entitled The Travels and Adventures of Three Princes of Serendip, the intellectual Horace Walpole described “Serendipity, a very expressive word,” as “discoveries, by accidents and sagacity, of things which they were not in quest of.”

Pievani knows a lot, but like a lot, about the history of science, and he puts it on display here. He quickly debunks all of the instances of alleged serendipity that are always trotted out: Fleming the microbiologist had been studying antibiotics and searching for a commercially viable one for years before his moldy plate led him to penicillin. Yes, Röntgen discovered X-rays by a fluke, but it was only because of the training he received in his studies of cathode rays that he recognized he was observing a new form of radiation. Plenty of people over the course of history splashed some volume of water out of the baths they were climbing into and watched apples fall, but only Archimedes—who had recently been tasked by his king to figure out if his crown was made entirely of gold—and Newton—polymathic inventor of calculus—leapt from these (probably apocryphal) mundane occurrences to their famous discoveries of density and gravity, respectively.

After dispensing with these tired old saws, Pievani then suggests some cases of potentially real—or strong, as he deems it—serendipity. George de Mestral’s inventing velcro after noticing burrs stuck to his pants while hiking in the Alps; he certainly wasn’t searching for anything, and he parlayed his observation into a useful technology. DuPont chemists’ developing nylon, Teflon, and Post-it notes while playing with polymers for assorted other purposes. Columbus “discovering” the Americas (for the fourth time) since he thought the Earth was about a third smaller than Eratosthenes of Cyrene had correctly calculated it to be almost two thousand years earlier, forgotten “due to memory loss and Eurocentric prejudices.”