Vanz Studio/iStock/Getty Images Plus

In the decades following the development of the GED test in 1942, when fewer than one in five adults held a college degree, the GED primarily functioned as a way to complete one’s education—an off-ramp from formal schooling.

Today, however, most jobs that once required only a high school education require additional training. For more than 24 million American adults who do not hold a high school diploma or equivalent credential, exams like the GED represent the primary second-chance pathway to access postsecondary educational opportunities. Increasingly, uncredentialed adults are using the GED as an on-ramp to college.

Recognizing its evolving role as a postsecondary pipeline, the GED Testing Service introduced two college-readiness designations in 2016. Students who score within certain subject test score ranges earn a GED College Ready (scores of 165–174) or GED College Ready + Credit (175–200) designation in that subject. The American Council on Education College Credit Recommendation Service recommends that students who earn a GED College Ready designation receive waivers from placement testing or remedial coursework in that subject. Furthermore, ACE recommends that students who qualify as GED College Ready + Credit receive college-level credits—similar to the process by which students earn credits for passing an Advanced Placement or College-Level Examination Program (CLEP) exam.

In theory, these college-readiness designations should help institutions identify those GED graduates most likely to succeed in college-level coursework while providing benefits that smooth qualifying students’ transitions to college. On GED.com, testers are told that those who earn a college-readiness designation “may be exempt from placement tests or remedial (non-credit) courses in college. This will save you money and help you earn your degree faster.”

Eight years after the 2016 introduction of the GED college-readiness designations, however, institutions remain largely unaware of their existence, and in a recent study I found no evidence that earning a GED College Ready or GED College Ready + Credit designation increases postsecondary attainment. What could be a powerful mechanism for smoothing the path to postsecondary education for a diverse pool of high-achieving students—a win-win for students and community colleges alike—is stalled.

An Information and Participation Gap

Even among experts in the field, I found knowledge of the GED college-readiness designations and their intended role in facilitating transitions to college for nontraditional students to be hazy at best. When I asked admissions officers, academic advisers and counselors at community colleges around the United States about whether their institution offered college credit to students who reached a GED College Ready + Credit benchmark in math or language arts, their answers were tentative and uncertain. A typical response was “Hmm … that’s a good question,” “I’m not familiar with that program” or “I’ll have to ask my supervisor.” Many administrators had detailed knowledge of institutional policies governing AP or CLEP exams but were wholly unfamiliar with the GED college-readiness designations.

While it is unclear how many institutions consider GED college-readiness designations in their course placement decisions, it seems that very few institutions award college credits to the highest-achieving GED scorers. Before retiring the ACE Credit College and University Partnerships Database in 2018, ACE identified only 26 colleges and universities that awarded college credits to students who earned a GED College Ready + Credit designation. Without willing institutional partners, many deserving GED graduates cannot receive the full benefits of earning a GED College Ready or GED College Ready + Credit score. In the absence of a wide network of partner institutions—and despite the program’s good intentions—my recent research shows that while college-ready GED graduates do enroll and persist in college at higher rates, the new GED college-readiness credentials themselves have done little to improve student enrollment, persistence or graduation.

In a nationally representative subsample of more than 15,000 people who took a GED subject test between 2014 and 2019, I found that while “college-ready” GED graduates enroll and persist in college at significantly higher rates than their lower-scoring peers who pass the GED test, testers who narrowly earn a GED college-readiness designation are no more likely to enroll in, persist in or graduate from college than those whose subject test scores fall just short of the college-readiness threshold. In other words, the GED college-readiness benchmarks predict—but do not cause—better college outcomes.

In an educational environment characterized by dropping or stagnating enrollments and stark declines in FAFSA completions, the unfulfilled potential of the GED College Ready credentials represents a missed opportunity for both college-ready GED graduates and the institutions where they might enroll and succeed. Prior studies suggest that this model can work. When students actually receive credit for prior learning via exam certification, they are more likely to complete postsecondary credentials.

A Potential Pipeline of Diverse, College-Ready Talent

While awareness of the GED college-readiness designations may be low, my research points to just how helpful they can be, in that scores above these thresholds are meaningful predicative indicators of which students are most likely to enroll and persist in college.

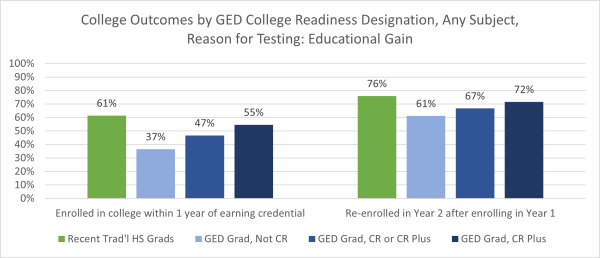

Over all, I found that more than 30 percent of all GED graduates enroll in college within one year of taking the test, and more than 60 percent of those college enrollees re-enroll for a second year. But college enrollment and persistence rates are even higher for college-ready GED graduates who say that educational gain is their primary motivation for taking the test: Among the highest-achieving, educationally motivated GED graduates, I found that college enrollment rates exceed 50 percent and second-year persistence rates exceed 70 percent—a far cry from 20 years ago, when GED’s own longitudinal analysis found that more than 75 percent of GED graduates who enrolled in college dropped out after a single semester. Impressive as these rates of enrollment and persistence may be, there is considerable scope for enrollment, retention and graduation rates to grow, as GED graduates still lag behind traditional high school graduates (see graph).

GED graduates who enroll in college are a diverse group of nontraditional students. In addition to serving students who have dropped out or interrupted their schooling, the GED test offers a way for home-schooled students and international students to validate their proficiency in high school–level content that is aligned to U.S. college- and career-readiness standards. GED graduates are older and more likely to come from underrepresented demographic groups. Strengthening programs that support nontraditional, disadvantaged students stands out as a potentially potent driver of educational equity.

For the community colleges that enroll the vast majority of GED graduates, institutional policies that make campuses a more attractive place for these nontraditional students—like by waiving remediation requirements for students who earn a GED College Ready designation or awarding elective credits to students who earn a GED College Ready + Credit designation—offer the potential to increase enrollments and enhance campus diversity along multiple dimensions while saving students time and money. For GED graduates who are deciding between multiple college options, institutional policies that smooth their transition to college, demonstrate respect for their prior learning and experience, and make college more affordable may influence their decision regarding whether and where to enroll, in addition to promoting their ultimate success.

Let this be a call to action for institutions to build a stronger infrastructure to support nontraditional students like GED graduates. System leaders and admissions officers need to know what the GED college-readiness designations mean, carefully consider whether and how to account for this evidence of students’ prior learning, and provide clear, easy-to-find guidance for students. As a parent organization of the GED Testing Service, ACE can also take an active role in promoting transparency by maintaining an accurate and up-to-date database of partner institutions that award credit for prior learning to college-ready GED graduates. Taking a more inclusive and transparent approach to awarding credit for prior learning can help make college campuses more welcoming to students who arrive via alternative pathways.