This post was originally published in 2019 and updated in 2024

by Terrell Heick

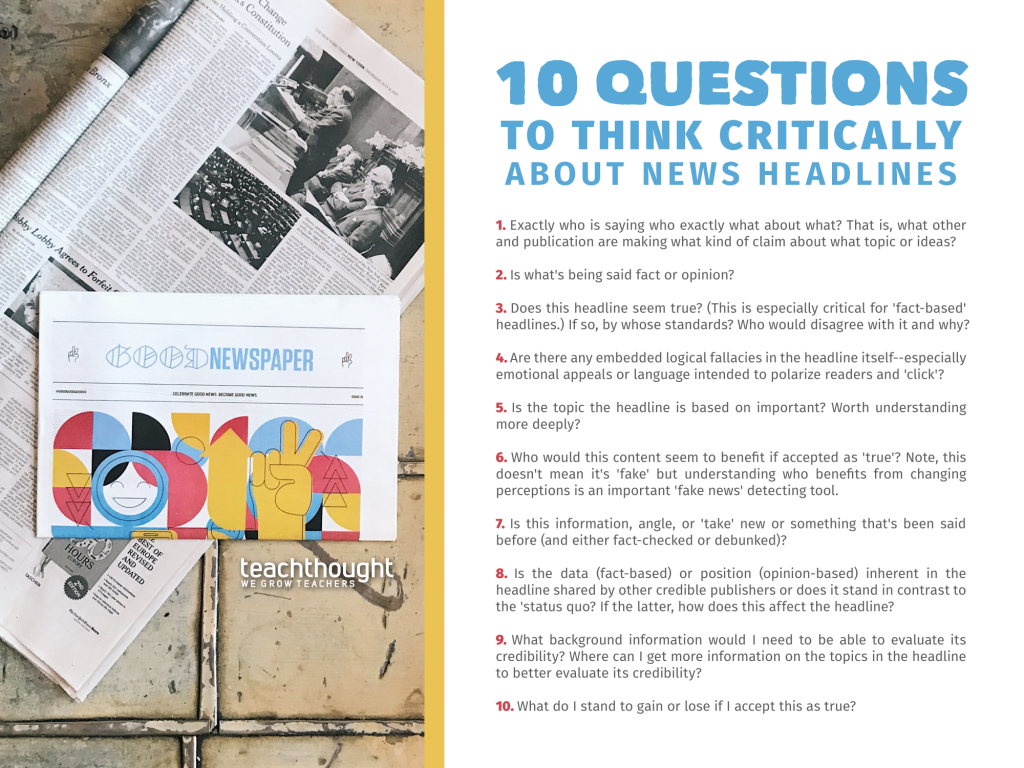

1. In the article, headline, or social share, ‘who’ is saying ‘what’? That is, what specific author and publication are making what kind of claim about what topic or ideas?

2. Is what’s being stated or claimed fact or opinion?

3. Does this headline seem true? (This is especially critical for ‘fact-based’ headlines.) If so, by whose standards? Who would disagree with it and why? How can it be fact-checked? Is the author using ‘grey areas’ of ‘truth’ in a way that seems designed to cause a stir, cast doubt, influence thinking, or otherwise change the opinion of readers?

4. Is this headline entirely ‘true’/accurate or based instead on partially true information/data? Misleading information is often based on partial truths and then reframed to fit a particular purpose: to cause an emotion such as anger or fear that leads to an outcome of some kind: a ‘like,’ donation, purchase, signup, vote, etc.

5. Are there any embedded logical fallacies in the headline itself–especially straw man arguments, emotional appeals, or charged language intended to polarize, rally, or otherwise ‘engage’ readers?

6. Is the topic the headline is based on important? Worth understanding more deeply?

7. Who would this seem to benefit if accepted as ‘true’?

8. Is this information, angle, or ‘take’ new or something that’s been said before (and either fact-checked or debunked)?

9. Is the data (fact-based) or position (opinion-based) inherent in the headline shared by other credible publishers or does it stand in contrast to the ‘status quo’? If the latter, how does this affect the headline?

10. What background information would I need to be able to evaluate its credibility? Where can I get more information on the topics in the headline to better evaluate its credibility? What do I stand to gain or lose if I accept this as true?

11. Does the ‘news story’ accurately represent the ‘big picture’ or is it something ‘cherry-picked’(in or out of context) designed to cause an emotional response in the reader?

For the second set of questions to think critically about news headlines, we’re turning to the News Literacy Project, a media standards project that created a set of questions to help students think critically about news headlines.

12. Gauge your emotional reaction. Is it strong? Are you angry? Are you intensely hoping that the information turns out to be true or false?

13. Reflect on how you encountered this. Was it promoted on a website? Did it show up in a social media feed? Was it sent to you by someone you know?

14. Consider the headline or message:

a. Does it use excessive punctuation or ALL CAPS for emphasis?

b. Does it claim containing a secret or telling you something that ‘the media’ doesn’t want you to know?

c. Don’t stop at the headline. Keep exploring!

15. Is this information designed for easy sharing, like a meme?

16. Consider the source of information:

a. Is it a well-known source?

b. Is there a byline (an author’s name) attached to this piece? Does that author have any specific expertise or experience?

c. Go to the website’s ‘About’ section. Does the site describe itself as a ‘fantasy news’ or ‘satirical news’ site? What else do you notice–or not notice?

17. Does the example you’re evaluating have a date on it?

18. Does the example cite a variety of sources, including official and expert sources? Does this example’s information appear in reports from (other) news outlets?

19. Does the example hyperlink to other quality sources?

20. Can you confirm, using a reverse image search, that any images in your example are authentic (i.e., haven’t been altered or taken from another context)?

21. If you searched for this example on a fact-checking site such as snopes.com, factcheck.org, or politifact.com, is there a fact-check that labels it as less than true?

Remember:

- It is easy to clone an existing website and create fake tweets to fool people

- AI and ‘deep fakes’ are become increasingly commonplace

- Bots are active on social media and are designed to dominate conversations and spread propaganda.

- Propaganda and/or misinformation often use a real image from an unrelated event.

- Debunk examples of misinformation whenever you see them. It’s good for democracy!

You can download the full ‘checkology’ pdf here and find more resources at checkology.org