Before writing a story, you should pick the story structure you want to follow. Story structure serves as a literary blueprint, guiding writers to captivate readers by including all vital story elements.

While this might sound like Mad Libs, some of the most famous authors, playwrights, and other storytellers use these storytelling structures. You can leverage story structures to enhance the plot, characters, and backstory, crafting a tale readers can’t put down.

In this blog, we’ll define what a story structure is, explain why it’s important, and provide examples of the most commonly used types.

Table of Contents

Why story structure is important

Tips for identifying story structures

What is story structure?

Story structure, sometimes called narrative or plot structure, is the framework within which the narrator tells a story. Writers use story structure as a template to ensure they have everything needed to tell a clear and entertaining story from beginning to end.

Following a story structure ensures that you include important details and avoid unnecessary elements that might distract or bore the reader.

While writers commonly use them, story structures are also used by public speakers, news anchors, filmmakers, and anyone with a story to tell. In fact, some of the examples we’ll cover date back to ancient Greece.

Before we continue, it’s important to note that story structure is different from story archetypes. Archetypes are universal patterns or character types, whereas structure refers to how those archetypes’ stories are told. For instance, rags to riches is an archetype that can be told through different story structures.

Why story structure is important

Story structure acts as the foundation of a narrative. It guarantees continuity, ensures that key themes and details are addressed, and helps the writer pinpoint essential literary elements like conflict or plot.

In other words, it helps create better stories. Without a proper structure, readers might get lost or confused and be tempted to put your book down. It helps convey key points, like the main conflict or overall theme, that keep them excited to continue reading.

Elements of story structure

Regardless of the order in which you tell a story, most stories contain the same five elements: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution.

Exposition

The exposition lays out the backstory, characters, setting, and plot. It should also introduce the protagonist. An example would be the first few pages of The Hunger Games, in which the reader is introduced to Katniss Everdeen, the world of Panem, and the concept of the Hunger Games.

Rising action

An inciting incident typically causes the rising action, or the event that causes a conflict. This story element should have tension and consequences for the protagonist. The inciting incident in The Hunger Games is Katniss volunteering for her sister, and the rising action consists of the battles and tribulations she goes through during the Hunger Games.

Climax

The climax is when the protagonist succeeds or sometimes fails in the conflict presented throughout the story. It’s also the scene that the entire book has been leading up to. In The Hunger Games, this would be Katniss’s successful takedown of the government.

Falling action

Falling action is the consequence or result of the climax. It’s the part in The Hunger Games where Katniss returns home after ending the Hunger Games and tries to live a normal life.

Resolution

Also known as the “denouement,” the resolution clears up any loose ends and explains how the protagonist and their world have changed because of the plot. In The Hunger Games trilogy, this would be the final chapter that describes Katniss’s life in the years after the climax.

Types of story structures

The type of story structure you pick can influence how and when you introduce certain elements into your writing. While there are many types, we’ll discuss the eight most common or important types found throughout literature and media.

Fichtean Curve

The Fichtean Curve is a story structure that emphasizes the rising action element, putting the protagonist through several tension-packed crises. Unlike other story structures, there’s little to no exposition at the beginning of a story. Instead, the reader learns about the protagonist and their world through the crises they face on their way to the climax.

The Wizard of Oz is a classic Fichtean Curve because it involves the protagonist, Dorothy, going through several crises (her dog being taken, the tornado, meeting the Wicked Witch, etc.), before the climax of defeating the witch and finally getting home.

The falling action shows how Dorothy is changed by the rising actions she experiences throughout the plot.

Three-Act

The Three-Act story structure is the one people are most familiar with because it’s often used in popular books and movies. Each act serves as a main component of the overall story, and each act is broken into three steps.

Act 1: Setup

Exposition: Introducing the characters and world. The main character and their background are introduced.

Inciting incident: Something happens to get the plot moving.

Plot point one: The protagonist decides to engage in the conflict.

Act 2: Confrontation

Rising action: There is tension between the protagonist and the antagonists.

Midpoint: The protagonist is almost foiled in their mission to resolve the conflict.

Plot point two: Following the midpoint, the protagonist is unsure if they can move on and fix the conflict.

Act 3: Resolution

Pre-climax: The character considers their options and decides to re-engage in the conflict with newfound optimism.

Climax: There’s another confrontation with the antagonist.

Resolution: The audience learns of the fallout from the climax, and a new world or status quo is introduced.

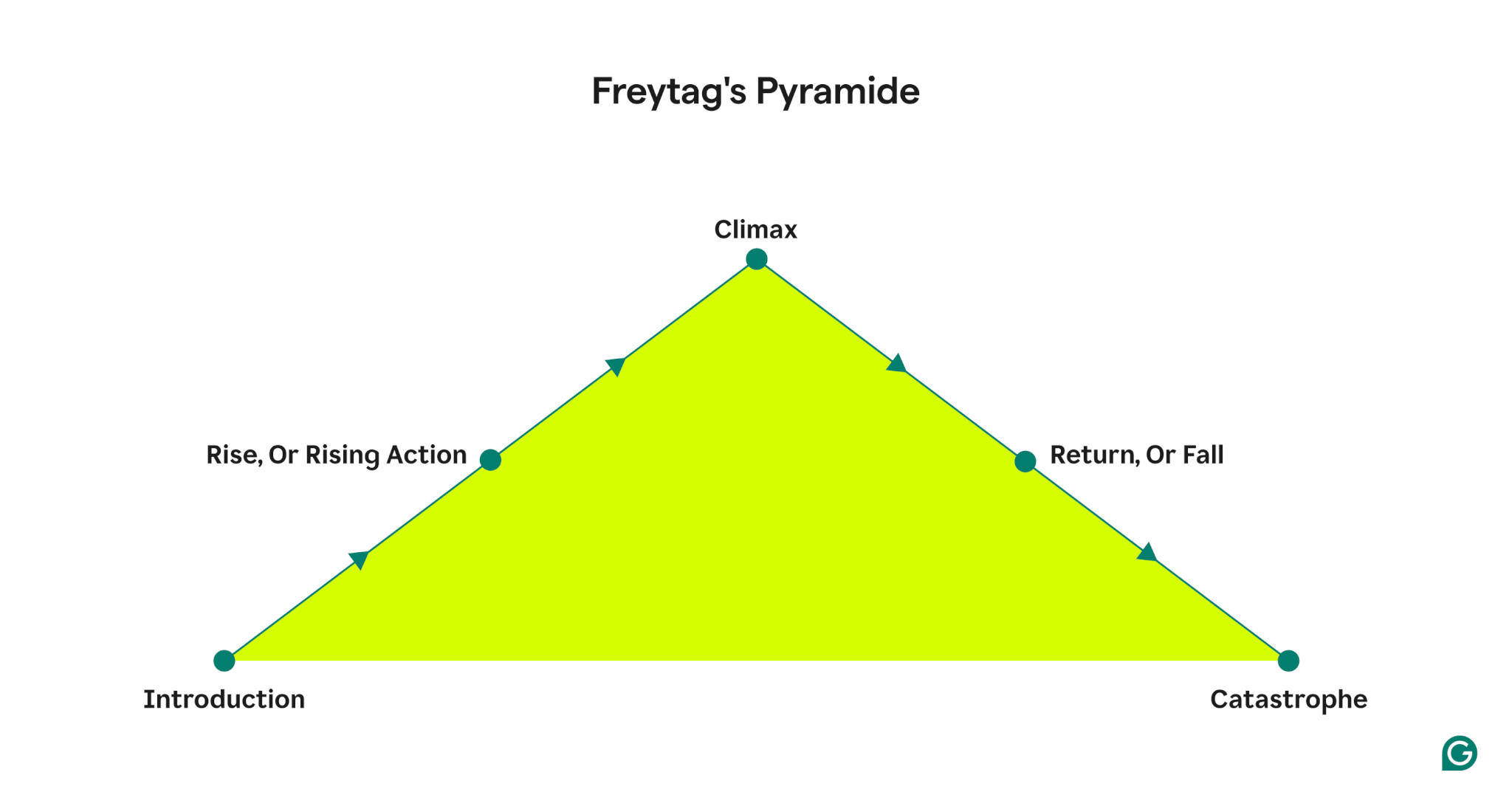

Freytag’s Pyramid

Freytag’s Pyramid is most commonly found in classic Greek tragedies and Shakespeare plays, though some modern-day books and movies still follow this story structure.

Exposition: The protagonist and their world are introduced, with the inciting incident occurring relatively early in the book or play.

Rising action: This takes up most of the narrative. The protagonist seeks to resolve the conflict through a series of events, with the tension and stakes increasing as time goes on.

Climax: The conflict must be resolved now. This is the point of no return.

Falling action: The consequences of the climax.

Resolution: If the story is a tragedy, this is the moment where the protagonist’s worst fears are realized, and they’re at their lowest point. In a comedy, it shows the results of their success in overcoming the main conflict.

Five-Act

The Five-Act story structure is similar to Freytag’s Pyramid. Some people use the terms interchangeably, but it’s good to know both.

Exposition: The status quo and basic plot premise are introduced.

Rising action: The protagonist faces a series of challenges.

Climax: The point of no return

Falling action: The fallout from the climax

Resolution or catastrophe: Depending on the type of story you’re writing, the protagonist emerges as the victor or loser, and the audience is introduced to a new world.

Hero’s Journey

The Hero’s Journey was first used in ancient mythology and can even be found in modern examples like Star Wars. There are 12 steps to the Hero’s Journey.

Ordinary world: The hero’s status quo is introduced.

Call of adventure: An inciting incident that calls on the hero to take on new challenges outside their comfort zone.

Refusal of the call: The protagonist is, at first, reluctant to take on these challenges.

Meeting the mentor: The protagonist meets a teacher, parent figure, or spiritual leader to help them on their journey.

Crossing the first threshold: The character, perhaps for the first time in their life, steps out of their comfort zone.

Tests, allies, enemies: They take on challenges, meet new friends, and are introduced to enemies they’ll fight along the way.

Approach to inmost cave: The protagonist approaches their goal.

The ordeal: A fight or test the protagonist engages in and wins.

Reward (seizing the sword): The protagonist obtains a new weapon or skill to help them with their goal.

The road back: The protagonist realizes there’s still more work to be done.

Resurrection: The climax or the final challenge the protagonist must face.

Return with the elixir: This is the falling action and resolution, where the protagonist emerges victorious and takes on a new life in their world.

Story Circle

Story Circle is a story structure commonly used by screenwriters and popularized by Dan Harmon, the creator of Rick and Morty and Community. It borrows from the Hero’s Journey structure without requiring the protagonist or other characters to be transformed, though the audience can still learn more about them through the rising actions they experience each episode.

Using this type of story structure requires the writer to have an intimate understanding of the character they’re trying to write about and the character arc they want to convey to the audience. It follows eight basic steps:

Zone of comfort: The character is in a status quo.

Want or need: The protagonist wants or needs something, which could result from an inciting incident.

Unfamiliar situation: The protagonist must search for the thing they want or need in an unfamiliar setting or situation.

Adapt: They begin to acclimate to their surroundings.

Find: They get the thing they were searching for.

Pay a heavy price: They realize it might not have been worth the trouble.

Return to status quo: They go back to their zone of comfort.

Change: They are changed by the unfamiliar situation they were in.

Seven-Point

The seven-point arc is a narrative story structure that resembles the Hero’s Journey or Three-Act structures, though it’s less strict in how the writer maps out the story.

The hook: During the exposition, something should draw the reader in and make them want to continue.

Plot point one: An inciting incident or call to adventure that causes the protagonist to leave their comfort zone.

Pinch point one: The protagonist meets the antagonist, and their conflict is revealed. The antagonist decides it’s their mission to resolve the issue.

Midpoint: The protagonist goes from being a passive to an active participant in the conflict.

Pinch point two: The protagonist and antagonist meet again, but the latter wins and seemingly

leaves the good guy defeated.

Plot point two: The protagonist discovers something that reinvigorates their spark to resolve the conflict.

Resolution: The conflict is resolved, and the protagonist’s character arc is tied up, showing how they’ve changed from the beginning to the end.

Save the Cat

The Save the Cat structure is primarily for screenplays because it’s laid out as a beat sheet with page numbers to show how many pages of a screenplay each part should take up. That said, it can be easily adapted to books or short stories.

Opening image: The opening shot or paragraph that describes the world the story is taking place in.

Setup: What is the daily life of your protagonist? What characters do they regularly interact with?

Theme stated: What is the theme of their story?

Catalyst: The inciting incident

Debate: The protagonist ignores the call to adventure.

Break into two: The protagonist decides to engage in the conflict.

B story: A subplot, usually comedic or romantic in nature.

The promise of the premise (fun and games): The protagonist has a few minutes of fun

before they’re pushed into the conflict.

Midpoint: A plot twist in the protagonist’s journey to resolve the conflict.

Bad guys close in: Increased conflict and tension due to advances from the antagonist

All is lost: The protagonist seemingly loses their battle.

Dark night of the soul: The protagonist hits rock bottom.

Break into three: The protagonist learns new information that boosts their spirit and confidence.

Finale: The protagonist uses their new information to defeat the antagonist in the climax.

Final image: The resolution. A new world and a transformed protagonist are shown to the audience.

Tips for identifying story structures

Here are five ways to identify story structures used in books, films, and other media.

Search for the exposition: Many story structures place the exposition of the characters and plot at the beginning, but others, like the Fichtean Curve and the Story Circle, may use other means to lay out their world.

Observe the pacing: Look at how the story builds tension from beginning to end. Does it start with a status quo world, or does it begin with a rising action or conflict?

Find the turning point: The turning point is typically an inciting incident that leads to the rising action. When does it happen in the story?

Analyze the plot: Look for key elements to identify the story structure. Is the protagonist searching for something like in the Save the Cat structure, or is there a call to adventure as in the Hero’s Journey?

Look at how the story ends: Are there consequences and fallout after the climax, like in the Hero’s Journey, or does it end like a Story Circle, where the character is not transformed?

Story structures FAQs

What are the elements of story structure?

The five elements of story structure are exposition (describing the plot, world, and characters), rising action (the tension and conflict between the protagonist and antagonist), climax (the point of no return), falling action (the fallout from the climax), and resolution (how the protagonist or world around them changed).

What is the three-act structure?

The Three-Act structure is a way of telling a story in three parts: Setup, Confrontation, and Resolution. Each act is broken into three steps to convey the characters, conflict, climax, and fallout from the climax.

What are the common story structures?

The eight most common story structures are Fichtean Curve, Three-Act, Freytag’s Pyramid, Five-Act, Hero’s Journey, Story Circle, Seven-Point, and Save the Cat.