Some employers use students’ grades as a screening tool in their applications, but research shows GPA alone is not the best indicator of a student’s future work performance.

miniseries/E+/Getty Images

Does being an honors student mean you’ll be a great employee? New research suggests maybe, but that’s not the only factor that matters.

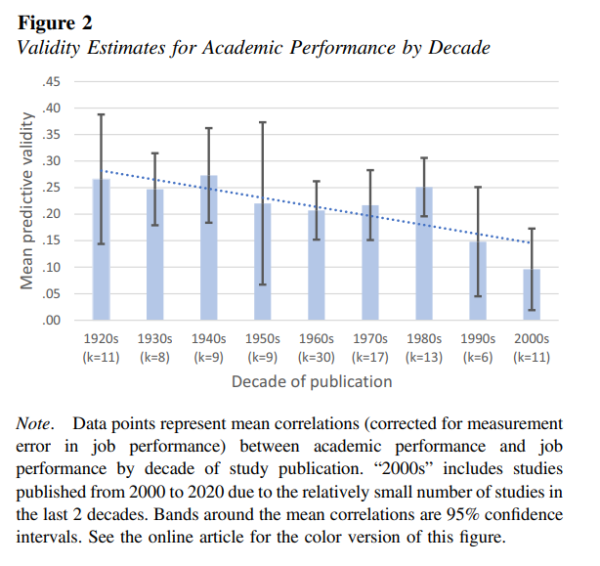

In a soon-to-publish article in the Journal of Applied Psychology, researchers from the University of Iowa identified that, since the 1920s, academic performance has weakened as a predictor of a graduate’s performance in job roles.

The study shows while there is still a predictive relationship between assessment measures in higher ed and assessment in the workplace, other, more specific measures may better define this relationship, such as relevant coursework and professor evaluations. Researchers believe this insight can better support curriculum development and connect academics to careers.

The background: Historically, academic performance has been recognized as a predictor of job performance because it can be a sign of motivation, effort and cognitive ability, as well as the acquisition of technical knowledge that can be relevant to future jobs.

More recently, public discourse has shifted away from this idea and instead said academic performance is not as useful as a predictor of job performance because academic content doesn’t translate to today’s work environment or because of grade inflation in higher education.

Employers’ use of GPA as a screening tool for hiring recent graduates has been on the decline for years, according to research from the National Association of Colleges and Employers. Since 2019, GPA as a screening factor has fallen 35 percentage points, says Mary Gatta, NACE’s director of research and public policy.

Instead, more hiring managers place emphasis on an applicant’s practical skills and career competencies such as problem-solving abilities, teamwork and written communication skills.

Researchers sought to understand how a student’s academic performance generalizes to performance in a workplace to better inform employers, instructors and students as they consider the role of grades.

To gauge the relationship between academics and work achievements, researchers evaluated other factors, including training performance, turnover, job relevance and professor ratings to see how they influenced predictions of job performance.

Methodology

For the meta-analysis, researchers focused on nine factors, such as studies that evaluated individuals’ academic performance, academic performance prior to work outcomes and jobs held after graduation. The studies measured academic performance in GPA, class rank or professor rating and job performance in supervisor and peer ratings or from trained observers.

Researchers evaluated 117 studies, including 58 journal articles, 41 dissertations and theses, 12 technical reports, three book chapters, and three conference papers in total.

The results: Ultimately, researchers found that academic performance did predict job performance and training performance. That predictive factor’s validity has declined over the past few decades, but researchers say that higher mean grades didn’t create smaller predictive validities. Instead, the decline is due to the measures used in recent studies that are all correlated with weaker predictive validity, such as less job-relevant measures or using student’s self-reported grades instead of official ones.

There was no relationship between academic performance and turnover, but researchers found a weak negative relationship between performance and intended turnover. So students who had higher demonstrated academic performance were less likely to have intentions to leave their workplace.

The study also found academic performance measures that were relevant to job functionality, such as grades earned in major courses or other relevant coursework, were better predictors of job performance compared to more general measures, such as grades in general education courses. Academic performance in graduate school was also a better predictor of job performance, compared to undergraduate performance.

Researchers identified, among ways institutions assessed students, professor ratings were the best predictors of job performance (compared to GPA and class rank), which could speak to the need for employers to capture additional information about students’ work in classes not measured by GPA, like effort or interpersonal skills.

So what? The study’s findings show that academic performance is most directly related to a graduate’s job performance when it reflects job-relevant coursework or when it uses professor evaluations.

Gatta affirms that grades still matter to employers, but the most important things for an applicant to demonstrate are key skills and knowledge developed in relevant areas, such as teamwork or leadership.

Researchers also see a need for more experiential learning in courses to provide hands-on learning and practice occupation-relevant behaviors, because it’s shown to be tied to future success.

More employers are saying internships offer the best return on investment, Gatta says, because it allows them to develop students’ skills while still in college, so partnerships between colleges and outside organizations can meet this need.

Do you have a career prep tip that might help others encourage student success? Tell us about it.