Cybersecurity professionals serving as chief information security officers (CISOs) continue to see respectable increases in pay, but not at the same rate as two years ago, and not in a way the keeps up with the changes to their responsibilities.

The average CISO now earns $403,000 in annual compensation — including salary, bonuses for reaching specific goals, and equity, such as stock options — representing a 6.4% increase over the past 12 months, according to IANS Research’s “2024 CISO Compensation Report” published on Oct. 2. However, changes to the threat landscape frequently put business operations under attack, the responsibility for which falls on the shoulders of the CISO, especially following rules issued by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) that requires CISOs to determine whether a breach is material within four days of discovery.

CISOs often do not have enough resources at heir disposal to do so, putting them in legal jeopardy, or, conversely, are successfully mitigating threats only to endure budget pressures because of that success, says Fred Kwong, vice president and CISO at DeVry University.

“There’s this dichotomy between, Hey, Fred’s doing a good job, keeping on top of the threats, mitigating the issues, [yet] at the same time [he’s] asking for more resources, more money, even when they’re seeing that the threat is not actualized,” he explains. “We’re kind of getting questioned, ‘Well, do we really need another person? Do we need really need another technology or control, because it seems like you have these things handled.'”

Kwong manages a team of five other cybersecurity professionals, but continues to fight to hire a sixth — even though the organization is unlikely to approve another full-time employee.

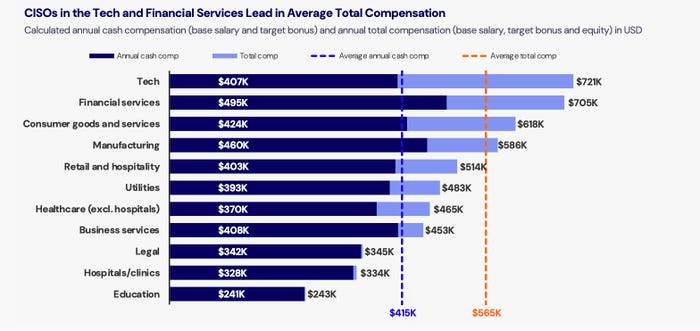

Source: 2024 CISO Compensation Report, IANS and Artico

In 2021 and 2022, following increased remote work due to the pandemic, companies found themselves needing to secure their operations infrastructure, driving demand for CISOs — especially as cybercriminals started compromising firms and infecting their systems with ransomware. While CISOs made significant gains in compensation during the tail end of the pandemic — 44% either switched jobs or took a retention bonus in 2022 — the demand now shows signs of settling down, with only 11% doing the same in 2024, says Nick Kakolowski, senior research director at IANS Research.

“We are seeing generally a lack of movement, mostly because of macroeconomic conditions — businesses are just being conservative about hiring more,” he says. “Businesses are kind of saying, We’ll get by with what we have for a while. We’ll hold off on hiring. We’ll keep on our current path, and more CISOs are staying put, rather than taking the risk of taking on something new right now.”

CISO Mindsets: A State of Stress

CISOs that move jobs — or are paid an incentive to stay in their current position — see the biggest increases in compensation, and CISOs for state governments are among the most likely to move. Nearly half of states hired a new CISOs in the past year, leading the average tenure of a CISO to drop from 30 months in 2022 to 23 months this year, according to the biennial Deloitte-NASCIO Cybersecurity Study.

Stress will only continue to build for CISOs in state government positions: Finding and retaining cybersecurity-skilled professionals is difficult, more sophisticated attacks — such as ransomware — have become common, and budgets continue to be tight and often hard-to-predict, says Srini Subramanian, principal with the risk and financial advisory group at consulting firm Deloitte.

Government cybersecurity professionals, which make between $125,000 to $225,000, typically do not include compensation in their Top 3 reasons for job satisfaction. Yet, increasing attacks and greater consequences for their networks, along with increased scrutiny for any outage or incident, puts them squarely in the in the eyes of the public and government officials, he says.

“The state-level systems are also dealing with … a lot more challenges compared to a private sector systems,” Subramanian says. “They have budget constraints, they have talent constraints, and now we are expanding the scope of the systems even more.”

Public Headaches, Private Stressors

Daniel Schwalbe used to work as a security pro under the CISO at the University of Washington, a large public university, which meant that his role bridged both government and education sectors. He loved the work, and he certainly wasn’t there for high pay, he says. Education CISOs are the lowest-paid of all the industries tracked by the IANS survey, with a median annual total compensation of $243,000 (the government sector was not listed).

Yet, the security work was neverending, he says.

“We had half a million devices on a network that we were supposed to protect, and I can tell you that on any given day, we pretty much figured there are 1,000 compromised devices on that network out of half a million,” he says. “That’s just the reality.”

When he left, it wasn’t about scoring a better salary, but about combatting the lack of a career path. The only position left for him to graduate to in the security career track at UW was CISO, but the current holder of that position did not intend to retire for at least three years. So, he accepted the job of deputy CISO with Farsight Security, and assumed the role of CISO at DomainTools when that company bought Farsight.

His responsibilities have changed somewhat. Compliance is more of an issue at a private firm, whereas the government and education sector have to deal with bureaucracy. Yet, making technology work better for security is a common factor, and he hopes that automation will reduce stress across the board.

“Investing a little bit upfront and tuning the alerts — so the stuff that actually comes out of your security tools is much more useful — can help,” he says. “It costs money, and it’s not a silver bullet, but in my opinion, it does help and can help with issues like threat analyst burnout.”

How AI Is Impacting Security

The research firms’ analyses also found that hot potato of AI risk is putting a lot of pressure on CISOs as individuals, escalating the stress. IANS Research’s Kakolowski says that, typically, no one security pro in the business is really well positioned to own AI. The right person needs a blend of technical, governance, privacy, and data-science backgrounds to really help organizations fully manage the risk, he says.

Usually, CISOs do not check all those boxes, which could expose them to liability.

“CISOs are becoming the go-to person to inform AI risk decisions, and there’s this pushback where CISOs say, ‘Well, we can’t own all of this risk, because this risk isn’t owned by the business unit,” he says. “‘Using the tooling, we can help inform you about this risk, and we can help you understand this risk, but you have to ultimately be the ones making that decision and taking that ownership.'”