When Columbia University President Minouche Shafik resigned abruptly on Wednesday, she became the third campus leader since December to step down amid Congressional pressure over how they handled sprawling student protests tied to the war between Israel and Hamas.

But unlike her peers, Liz Magill of the University of Pennsylvania and Harvard’s Claudine Gay, who stepped down soon after their widely criticized performance before lawmakers last year, Shafik seemed to be in the clear. Following her own grueling inquisition by the House Education and Workforce Committee in April, she weathered the wrath of lawmakers, students, faculty and alumni, but maintained the support of Columbia’s board of trustees.

So why did she bow out now, just weeks before the start of the fall semester and during a period of relative calm on campus? The move seemed more likely in a turbulent spring semester, when students set up an encampment on campus and occupied an administrative building, resulting in dozens of arrests, and sharp scrutiny of Shafik.

Thus far, Columbia administrators have had little to say about the timing of her exit. Shafik, in her resignation letter, touched lightly on the matter: “Over the summer, I have been able to reflect and have decided that my moving on at this point would best enable Columbia to traverse the challenges ahead. I am making this announcement now so that new leadership can be in place before the new term begins,” she wrote.

Columbia University did not respond to questions about Shafik’s resignation.

Now Shafik plans to work with the United Kingdom’s Foreign Secretary in an international development role, an area where she has experience, and a job she set up before announcing her departure. Shafik, who holds British, American and Egyptian citizenship, was already a member of the U.K. House of Lords. But it is not clear when talks began for her return to London; the Foreign Secretary’s office did not respond to a request for comment from Inside Higher Ed.

Terrence Casey, a professor of political science at Indiana’s Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology, wrote by email that given Shafik’s “life peer” appointment to Parliament’s upper house in 2020, “there really is no vetting process for Dr. Shafik” to accept a role in the U.K.

Janet Laible, a professor of political science at Lehigh University in Pennsylvania, wrote by email “that since the current [U.K.] government was only appointed after winning elections on July 4, there would not have been any formal communication with her before that.” Still, Laible added, “that is not to say that there was no *informal* communication” between Shafik and the U.K. government.

When Shafik stepped down, Dr. Katrina Armstrong was announced as interim on the same night. A Columbia administrator and professor, Armstrong will be at the helm when the fall semester begins in early September—and students have made it clear that protests are likely to resume.

Students for Justice in Palestine, a group active in campus protests, has warned that any leader who spurns their demands to divest from Israel and those profiting off the war “will end up exactly as President Shafik did.”

Shafik angered protesters by failing to act on their divestment demands, as well as by allowing police on campus to clear Hamilton Hall, the building they occupied, and arrest those inside. Faculty have likewise expressed outrage over both Shafik’s handling of the occupation and her performance on Capitol Hill, where many believe she failed to defend professors targeted by Congress.

“President Minouche Shafik threw me under the bus when she testified before Congress, but I’m still an employee of Columbia University, she’s not. Turns out that capitulating to the bullies didn’t work out well for her. It never does,” Columbia faculty member Katherine Franke wrote on X, referring to Shafik’s acquiescence to Congressional criticism.

Congressional Republicans also blasted Shafik for not cracking down on protesters sooner. On Wednesday night, Several GOP critics took a victory lap as news of Shafik’s resignation spread.

In the immediate aftermath of her resignation, free speech advocacy organizations and the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) condemned Shafik’s leadership at Columbia.

“By suppressing academic freedom and the free speech rights of students and faculty and inviting punitive discipline and a brutal police crackdown on student protests at Columbia, Shafik failed to protect basic tenets of higher education and capitulated to a new McCarthyist witch hunt against the Academy,” AAUP President Todd Wolfson said Thursday. “This is her legacy.”

How We Got Here

Shafik’s resignation was preceded by Liz Magill stepping down as president of Penn in December and Claudine Gay resigning the top job at Harvard in January. Both succumbed to public anger over their disastrous performance at the first Congressional hearing on campus antisemitism, when they and Massachusetts Institute of Technology President Sally Kornbluth gave legalistic and equivocating answers to a hypothetical question about calls for the genocide of Jews on campus. Only Kornbluth, who is Jewish, managed to hold onto her job at MIT.

Shafik had been asked to appear before Congress at that hearing in December, but was unable to do so because she was traveling overseas.

Instead, Shafik received a hearing of her own in April. Flanked by members of Columbia’s Board of Trustees and co-chair of the university’s antisemitism task force, Shafik largely avoided the missteps of her predecessors in the hot seat. When asked the same question that stymied her peers—whether calling for the genocide of Jewish people would violate university policies—Shafik stated clearly that it would at Columbia.

But even as she temporarily escaped the fury of Congress, Shafik outraged many Columbia faculty members who believed she threw them under the bus. And as she was testifying, pro-Palestinian protesters set up an encampment on Columbia’s campus, which would soon spark a wave of similar demonstrations at colleges coast to coast.

Congress held a third hearing on campus antisemitism in May, featuring the presidents of Northwestern University, Rutgers University and the University of California at Los Angeles. Where are they now? Here’s a look at the other six presidents who spoke to Congress, and what happened afterward.

Liz Magill

Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images

The Penn president was the first to go. Already under fire for her initial statements on the Israel-Hamas war—and for allowing a Palestinian literary festival to proceed on campus—she apologized and sought to clarify her remarks from the Congressional hearing. But the damage was done; Magill resigned in December amid withering criticism from Congressional Republicans and donors, who threatened to close their checkbooks should she remain at Penn. She had been in the role for a little more than a year.

Penn Board of Trustees chair Scott Bok also stepped down following Magill’s resignation, issuing a warning about allowing donors to wield too much influence.

Claudine Gay

Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images

Harvard’s first Black president survived the Congressional hearing only to be felled by another scandal.

Like Magill, she apologized for her missteps before Congress and seemed poised to keep her job until accusations of plagiarism suddenly emerged in December. Harvard initially batted away allegations trafficked by conservative activists but the clamor soon became too loud to ignore; Gay submitted corrections and acknowledged mistakes.

But it failed to placate the critics, and she resigned in January. Afterward, the former Harvard president defended herself, acknowledging she had made some mistakes but arguing that the effort to oust her was racially motivated.

Gay, who has retained a tenured faculty role, was president of Harvard for less than a year.

Sally Kornbluth

Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images

Of the first three presidents to speak to Congress, Kornbluth emerged relatively unscathed.

Like her peers, Kornbluth apologized for her missteps in the December hearing. That apology, and a subsequent plan to improve the campus climate by rethinking student disciplinary processes, free expression policies, and diversity, equity and inclusion programs—as well as by launching quality-of-life surveys for students and employees—seemed to satisfy her critics.

At the time of the hearing, Kornbluth, too, was relatively new to the job, with less than a year under her belt as MIT’s president. She is unique, however, in keeping her position despite the fallout.

Gene Block

University of California at Los Angeles

When the UCLA chancellor spoke to Congress at the third antisemitism hearing in May, he was already on the way out, having announced last August his intent to retire at the end of the academic year. Block, who is Jewish, led UCLA for nearly two decades. But his last year in the job was marred by violence at campus protests.

Block faced criticism from Congress for allowing a large pro-Palestinian encampment to grow on the UCLA campus, a site that later came under attack from pro-Israel counter demonstrators. Violent clashes erupted and videos of pro-Palestinian protesters blocking Jewish students from accessing parts of campus went viral, prompting Congress to haul Block in for questioning.

Flanked by the presidents of Northwestern and Rutgers, the long-time UCLA leader and his peers stood their ground at the hearing, pushing back at times in response to pointed questions.

Block stepped down last month as planned.

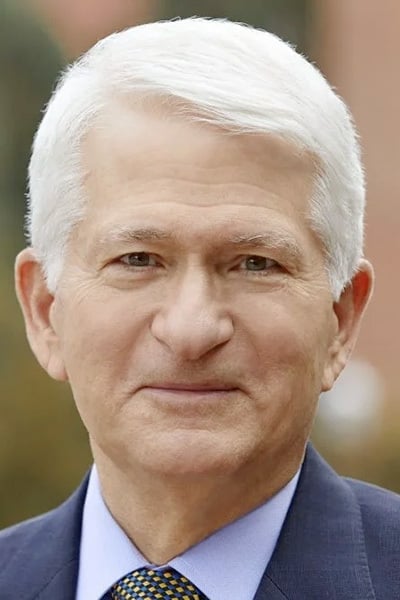

Michael Schill

Congressional Republicans took aim at Northwestern’s president during the May hearing—and missed.

Schill was a frequent target at that hearing, with Republicans pressing him about striking a deal with protesters to take down an encampment in exchange for more transparency on investments, scholarships for Palestinian undergraduates and other concessions. They also took issue with the speech and conduct of some Northwestern faculty members, and the university’s business dealings with Qatar.

But Schill pushed back, rejecting the premise of several questions and refusing to discuss individual faculty members or to comment on student speech.

Schill, who has led Northwestern since fall 2022, remains in his role as president.

Jonathan Holloway

Fresh off of an agreement with campus protesters to remove an encampment in exchange for a discussion about university investment policies and other concessions, the Rutgers president, who has said he opposes divestment, was also called before Congress in May.

Republicans accused both Schill and Holloway of making “shocking concessions to the unlawful antisemitic encampments on their campuses” when they first called the presidents in to testify. But at the hearing, Holloway rejected the notion he made concessions to a mob, as Congress alleged, emphasizing that he was speaking with his students and seeking to minimize disruption.

He was evasive at times, prompting Republican representative Bob Good to ask pointedly: “Are you in a position to answer any questions? Do you have an opinion on anything?”

Despite that criticism, Holloway managed to avoid the major missteps and viral moments that upended other presidents.

Holloway, who has led the university since 2020, remains president of Rutgers.